Karol Stefan Frycz (1910–1942) was one of the most eminent and original political journalists of the interwar period. His reflections focused on the concept of Central and Eastern Europe forming a strong geopolitical centre with Poland and Hungary at its core.

Karol Frycz was born in 1910 in Kielce. His father Stanislaw was a Supreme Court judge. Karol also graduated in law, and in 1939 he received his doctorate from the University of Warsaw. In his university days, he was active in the nationalist organisation known as the All-Polish Youth, to later become involved in the most prominent party of the Second Polish Republic – the National Party. He wrote articles for prestigious political and literary magazines. In his historiosophical deliberations, Frycz underlined that "the Romano-Latin civilisation developed in the shadow of the Cross and its further development is dependent on the fidelity to that Cross." In this context, he placed great value on the Baroque period and the Counter-Reformation, while the Sarmatian tradition and the legacy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were of key importance to him in relation to Poland's history.

Karol Frycz called for the unity of Central Europe stretching from the Baltic to the Adriatic and the Black Sea. In his eyes, the obstacle to this plan was the great cultural diversity of the various nations comprising Central Europe, which was particularly visible in relation to the Balkans – and countries such as Romania, Serbia, Bulgaria and Hungary. He emphasised that Hungary, occupying a key position on the Danube, was at the heart of Central Europe. It was on the Danube that the fate of Poland and Hungary was often decided. An unmistakable symbol of the shared fate of these two nations was the reign of the kings of the Jagiellonian dynasty in Hungary, as well as the Battle of Mohács (1526) and the Battle of Vienna (1683).

Karol Frycz was planning to write a book about Hungary entitled "The Problem of Hungary" at the behest of the Foundation Institute for Eastern Studies. In this publication, he wanted to place particular emphasis on Germany–Hungary relations. He was critical of Hungary's foreign policy in the 1930s, which led to Hungary becoming subordinate to Germany. Unfortunately, the Institute's plans did not come to fruition due to the outbreak of the war. Being a Polish patriot and a nationalist, Frycz made an attempt to define the character of the Hungarian nation. In his opinion, fate was decisive to Árpád leading the Turanian people of Asian origin to their new homeland in a location which showed the character of the country and its exotic charm to the fullest – among the steppes located in central Europe and surrounded with tall mountain ranges. Hungary meets the expectations of the ancient Greeks in relation to an ideal geographical location – a valley surrounded by mountains with a poetic shape of a shield. None of the countries of central-western Europe – wrote Frycz – satisfy our aesthetic sensibilities as much as Hungary does.

He underlined that Árpád was the leader of destructive and vindictive tribes and it was only the defeat of the Hungarians in the Battle of Lechfeld by the forces of King Otto I the Great that made them into a settled people. Soon after, the magnificent nation of King Saint Stephen was founded and starting with the 14th century Hungary became a fortress of European civilisation.

Karol Frycz saw the key to understanding the Hungarian spirit in the fact that this nation founded its state by conquest in the heart of Europe and the Slavic region and then did not disappear into the surrounding realms of ethnically disparate peoples. The feeling of estrangement and distinctiveness also created a rather strong antagonism between Hungary and the Slavic nations, instead of a typical sense of connection and solidarity. This situation even had a negative impact on the relations between Poland and Hungary, nations with historical fraternal ties.

The Polish columnist considered this powerful sense of distinctiveness to be the core of the national character of Hungarians. It is strongly aristocratic, which has both positive and negative aspects. This aristocratism is expressed in the feeling of pride and separateness resulting from the original alienation. The Hungarian psyche was shaped by pride combined with the conviction of one's own superiority. The Hungarians are also characterised by a sense of responsibility for the fate of their country, which generates a strong understanding of its historical mission and attachment to a land that has been the homeland and a place where the Hungarian civilisation was built through a thousand years of endeavour. Other national traits of the Hungarians include respect for the law and tradition. They are rightly considered a "nation of jurists", which while introducing reforms does not seek to demolish and build everything anew. Karol Frycz emphasised the Hungarian energy and perseverance, which verges on steadfastness and obstinacy, which allows the Hungarians to cut their coat according to the cloth. Thanks to their unrelenting perseverance when undertaking a task, the concept of discouragement is alien to Hungarian nature.

According to Karol Frycz, Hungarian patriotism also has its source in the recognition of the country's conquest and the resulting feeling of alienation from its neighbours. Hungarians remember that what is gained must always be defended, and simultaneously they are very proud of themselves and their beautiful country.

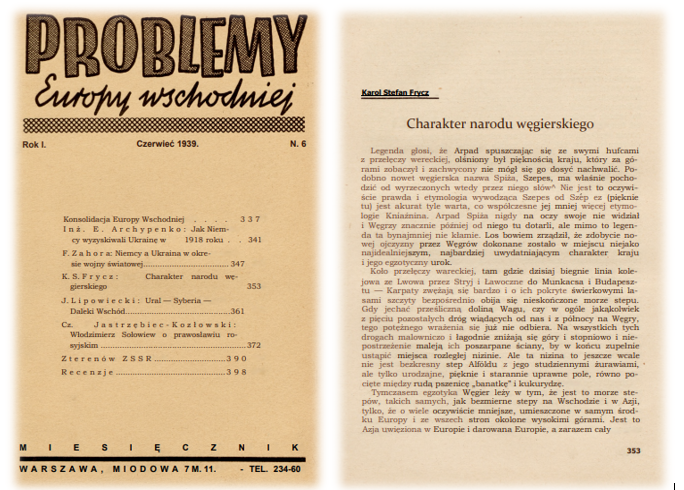

Article by Karol Stefan Frycz in the monthly Problems of Eastern Europe – June 1939

Karol Frycz wrote: "You must be able to see this beautiful country to fully appreciate its charm and captivating beauty. You must know its hot, caring sun, the heat of its steppes and the shadows of its forests. To drink its golden wine to the sounds of longing and passionately disconcerting music, to be able to understand everything and know that there will always be a fairy tale on earth and that romanticism will never die." (Karol Stefan Frycz, The Character of the Hungarian Nation, Problems of Eastern Europe 1939, no. 6).

Karol Frycz was arrested in September 1940 by the Gestapo. On 22 September, he was sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Thanks to his wife's efforts, he was released two months later. He used this time to complete the first part of his historiosophical work "True Poland". In it, he outlined the foundations of Polish national ideals based on Christian universalism, which he considered different from the pagan and esoteric German nationalist viewpoint. The Germans arrested him again on 19 April 1942 and sent him back to Auschwitz. Karol Frycz was shot against the wall designated for execution on 27 May 1942. He left behind his wife and infant daughter.

dr Krzysztof Kawęcki