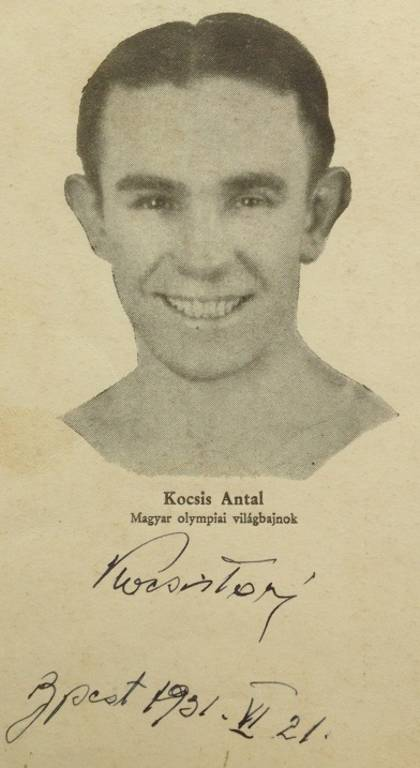

The IX Summer Olympic Games in Amsterdam were celebrated in late July and early August 1928, eight years after the signing of the Treaty of Trianon. Two boxers squared up to each other in the final bout, with a gold medal at stake: Antal Kocsis representing Hungary and Armand Apell, a Frenchman born in Strasburg. Kocsis triumphed and became the first Hungarian Olympic gold medal winner in boxing. After the fight, with tears in his eyes he wrote on a commemorative card: "For the Treaty of Trianon! Long live Hungary!"

Antal Kocsis was born on 15 November 1905, in the town of Kispest (a district of Budapest since 1950). First he tried his hand at competitive swimming, then wrestling. At the age of eighteen he began training for boxing. A year later he joined the Ferencvárosi Torna Club. His first major success came in 1926, when he became the Hungarian Champion. Then he won second place at the European Championships in Berlin. Between 1925 and 1929 he represented Hungary on as many as twenty occasions. During that period he did not succumb even once on his home ground. He fought in the flyweight class, for the lightest boxers (up to 50.802 kilograms).

In summer 1928 he represented Hungary at the Amsterdam Olympic Games. One hundred and forty athletes from thirty one countries competed in the tournament. In the first round Kocsis flawlessly did away with the Spaniard José Villanova. In the following rounds he triumphed over Hubert Ausbock from Germany and Carlo Covagnioliegi from Italy. The latter fight was the most harrowing thus far. "He was so strong I thought my head would fall off after one of his punches" – said Kocsis after the fight. In the final, the Hungarian was to meet Armand Apell, a Frenchman born in Strasburg. This fight had an additional dimension to it for Kocsis. His opponent was to represent France – the country which eight years before had a decisive hand in the disintegration of Magna Hungaria. Kocsis slept for just a few minutes on the night before the fight. He spent the time wandering hotel corridors and thinking things over, rather than in bed. In the meantime, Hungarian diplomacy and sports activists were doing their best to persuade the organisers to ensure the judges were as impartial as possible. The final bout finally began. The judges scored the first round for Apell. Kocsis was better in the second. The Hungarian champion kicked off the decisive, third round on the offensive. His punches were finding their target. After the fight the judges deliberated for three minutes. Finally the result was announced: Kocsis had won! Upon hearing the verdict, the Hungarian broke down in tears. Count Gyula Andrássy, present at the fight, congratulated him on the victory through tears of happiness. The thrilled Hungarian fans carried the Olympic champion around the sports hall for fifteen minutes. Gyula Vadas, the editor-in-chief and publisher of the newspaper "Nemzeti Sport", came to visit the winner in the changing rooms. The journalist described these moments in his memories:

"Everyone in the changing rooms wants to shake Kocsis' hand, many Hungarians are screaming with joy. I am watching Kocsis. I want to know what the new world champion us thinking about in this exciting moment, when the fight is still in his memory. But he wasn't even able to summarize his thoughts. I put down my diary in front of him and ask him to write something in it. He is still panting, leaning on the table and thinking. Then he starts writing, but he can hardly hold the pencil in his hand. Not too smoothly, not too prettily, but he is writing. He makes mistakes. Slightly embarrassed I encourage him: No problem. I'll fix that. He continues writing. He stops, lowers his head and I notice him crying. Tears are running down the pages of the diary. I tell him that I'll see what he wrote. And I read: "For the Treaty of Trianon! Long live Hungary!" A good Hungarian boy. Poor, simple kid, still in a trance after the fight, sweating, crying, his first thought was his homeland."

After returning home at the Budapest railway station, the winner was greeted by a cheering crowd of supporters. They tried to take the Amsterdam hero out from the train to the platform through a window. It took as many as fifty cops to control the situation. The activists of his beloved club were waiting for him with a green and white ribbon and a huge bouquet of roses with the inscription: "For the one who fights the heart - Ferencváros." Kocsis believed that every Hungarian in his place would fight to the end. His victory was not only sporting, but was to raise the spirits of his compatriots. In an interview with one of the newspapers he said: "If they took our country, our weapons, then they could see how strong our bare fists were. I really felt what a torn, destroyed country I come from. We had to show that our courage is in the right place." The success of the boxer had contributed to a huge increase in interest in boxing in Hungary. As a result, in 1930 and 1934 Budapest hosted the European Boxing Championships.

A year later, Kocsis won another national champion title. However, this did not prevent him from emigrating from the country for economic reasons. He settled first in South America and then in the United States, where he became a professional boxer. In his debut in exile in June 1930, Kocsis, called "the Hungarian boy" by local newspapers, defeated the Italian boxer Matti Disanti. His victory was celebrated in the stands by a large group of his compatriots. The crowning achievement of his career was fourth place in world ranking of boxers in his weight class. In 1935, the thirty-year-old Antal Kocsis retired from sports. The balance of his fights is twenty-two wins (four by knockout), thirteen losses (three by knockout) and five draws.

He and his family settled in Titusville, Florida. He worked as a carpenter and then as a tailor. He was repeatedly tormented by the longing for his family home and homeland. Antal Kocsis returned to Budapest several times. He saw Hungary for the first time again more than thirty years after his departure - in 1965. He visited Hungary over nine years during preparations for the seventieth-fifth birthday celebration of Ferencvárosi Torna Club. It was then that he explained to young boxing enthusiasts what it meant for an athlete to wear the green and white colour of Fradi for five years, when he was most successful: "Ferencvárosi Torna Club was my second home. I was always happy to wear a Fradi shirt. I'm very proud to be the first Ferencvárosi Olympic champion." When he returned to the United States, he reminisced: "Now away from my homeland, I love my sports fans and I will never forget the party they gave me when I visited Budapest. It was good to know that I'm still remembered, not forgotten. Now I'm living my retirement years modestly and I hope to see my friends from Fradi again. I spent many pleasant Sundays on the pitch and in the club. I still remember the fun after the victorious matches when we danced and listened to Fradi Woggenhuber's autumn songs... It would be nice to sing with you again in my life. Maybe I could even experience it. Now, as I write these words, I'm looking out the window. The weather is beautiful, all green, bushes, grass... The really green and white is not only our heart but also our soul..." Before his death, Kocsis lived in a retirement home in Florida, where he died on October 25, 1994, shortly before his eighty-ninth birthday. According to his wish, his ashes were scattered in the sea. In 1996, a marble plaque was unveiled on the wall of a house on Baross Street – the place where he was born. His bust stands on a promenade behind the swimming pool in the Ferencvarosi Torna Club sports centre.

Michał Kawęcki