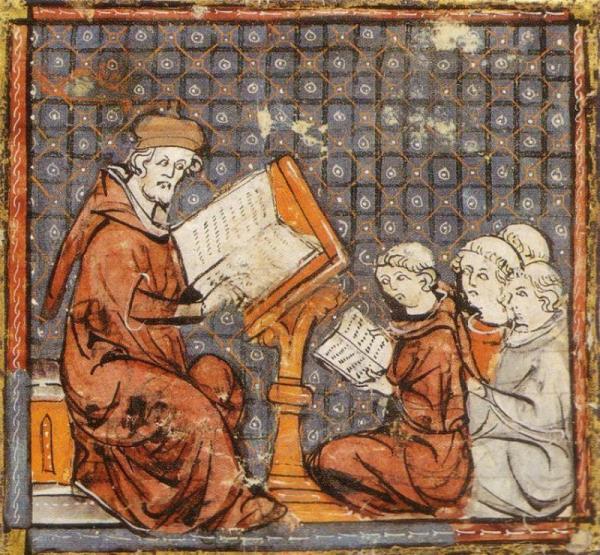

The ancients were already aware that to a large extent, every political community depended on its intellectual resources to facilitate permanence and development opportunities. As it entails the ability to formulate goals, assume certain positions and argue one's case. The idea of an organised academy became somewhat lost during the Middle Ages. However, once back in favour, it assumed a new shape. And knowledge ascended into due splendour. The studium generale institution was created, subsequently referred to as university.

Ever since the outset, the academic fate of East and Central Europe was largely peripheral. Even though a university was established in Prague in 1348, no such further institutions were founded in this region of Europe for some time to come. And today there are voices calling for an inclusion of these educational establishments into the academic "mainstream" and to improve their ratings.

Here I present the reader with two sketches on universities in East and Central Europe. Therein I delve deeper than usual into the consequences of that peripheral nature. I point out the strength which flows from assuming such a position and suggest that often that strength remains at the beck and call of intellectual of political sovereignty of national and political communities. In this case the "fac de necessitate virtutem" is worthy of deeper thought. The first sketch is devoted to the historic fate of the university idea in this part of Europe, and to the university in Kraków in particular. The second outlines the significance of Polish and Czech thought during the Council of Constance. I draw conclusions out of those historic premises on the contemporary situation, not just concerning universities, but the general intellectual state of our societies.

Part I

"SCIENCE SEEMS TO HAVE BEEN EXILED FROM THESE AREAS"

"Let there, then, be the pearl of teachings, that it may yield men steeped in knowledge, virtuous and skilled. May a refreshing source be opened, and may all learn to drink from its fullness seeking to quench their thirst for knowledge. Let all the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Poland and the neighbouring countries, as well as others from all over the world, come to this city of Kraków freely and safely."

This is what the Polish king wrote in the foundation act of the Kraków University of 12 May 1364. The document was edited by royal collaborators, royal chancellor Janusz Suchywilk and - probably - archbishop Jarosław Bogoria and Florian from Mokrsko. It was then copied by the court writer Jan from Ossów. In the university, then still called the studium generale (the name "university" became popular later), there was to be a department of law (consisting of five departments of Roman law and three of canonical law), medicine (two departments), and liberal arts (one department). The masters employed there were to earn between 20 and 40 grzywnas a year and have the right to housing facilities. A certain Jew from Kraków was pointed out to Freshers, who had the right to provide them with loans, but could not collect more interest than one grosz per grzywna a month. Freshers could also freely enter and leave the city and transport food and possessions without paying the slightest duty.

The establishment of the university in Kraków was the result of long-lasting requests and insistence of the Polish king on the Pope. In medieval Europe it was customary that a studium generale had the consent of the Pope or the Emperor, who was a representative of one of the two greatest powers, which were also fiercely competing for dominance in Europe. In this sense, the university was under strong political pressure from the outset. In fact, its establishment also depended on the state of public affairs, it was the result of long-term processes of crystallization of social strata and the laws governing the state. Hence, its establishment was usually preceded by a political reform of the state and a strengthening of the bourgeoisie. Central Europe was ruled at that time by rulers-legislators. In Denmark it was Waldemar IV Atterdag, in the Czech Republic it was Charles IV, in Poland it was Casimir the Great, in Hungary it was Charles Robert and Ludwig of Anjou, in Serbia it was Stefan Duszan.

During the time we are interested in here (13th-14th centuries), the inhabitants of Central and Eastern Europe could only observe how the West was covered by a dense university network Perugia, Siena, Rome, Florence, Pisa, Pisa, Pavia, Ferrara - all these cities of urbanised, northern and central Italy had their own universities. Universities were also established in France and Spain (although not always becoming vibrant academic centres, sometimes getting bogged down in organisational stagnation). Meanwhile, our European region of Europe still did not have a university. Waclaw II of Bohemia's actions, which he undertook in this direction, failed due to the resistance of powerful lords, who were afraid of strengthening the clergy in Bohemia. It was not until 1348 that Charles IV, King of Bohemia and the German Reich, established a studium generale in Prague. His old relationship with Pope Clement VI and his friendly contacts with Italy and France were conducive to this. The wealth of the Czech Republic at that time provided the university with financial stability. From the very beginning it was a strong university with all the faculties of theology, law, medicine and liberal arts. This fresh, one might say, University of Prague strengthened the position of the Czech king. This mobilized rulers who were in conflict with him, or those fighting for greater independence. Therefore, this issue was lively discussed live the court of Casimir the Great, but also at the court of the Anjouns and the Habsburgs. However, the case became bogged down. It was not until the pontificate of Urban V, the Pope, who remained a strict Benedictine monk and a man of science, that the university foundation in Kraków, but also in Vienna (1365) and Pécs (1367) became possible. Addressing the Pope with an urgent request to establish a studium, Polish delegates stated that "science seems to have been exiled from these areas"[1].

Finally, the university was established. Casimir the Great died in November 1370, however, and his death made it impossible to provide the university with a solid foundation (financial and human resources). Hence, there is no certainty when the studium generale actually started to function here. It is commonly believed that its renewal took place after the death of Queen Hedwig, who in her will enshrined appropriate measures for this purpose. It is possible, however, that the university was founded around 1390 and started to develop at that time. Queen Hedwig's will would therefore support rather than initiate this process. The process of obtaining rights to teach theology in Kraków, supported by Jadwiga and during her lifetime, also lasted for many years. This right was granted to the university by Pope Boniface IX with a bull from January 11, 1397.

In 1401, 203 students started their studies in Kraków. They came mainly from Małopolska, Silesia and Teutonic Prussia. The legal assumptions of the renewed university still referred to the Act of Casimir the Great of 1364, but in the new Act of 26 July 1400 King Władysław Jagiełło emphasized that the aim of the university is the Christianization of Lithuanian lands and the organization of the Church in Lithuania. The idea was to prepare the appropriate hosts for the Catholic clergy. The king also wanted Kraków to be for the Polish kingdom what Paris was for France, Bologna and Padua for Italy, Prague for the Czech Republic and Oxford for the Anglo-Saxon countries. The terms used to describe the activities of these universities are "radiate", "make respectable", "strengthen", "decorate", "enlighten", "elevate", "explain" and "fertilize"[2].

To understand the importance of these processes, one should remember that the Middle Ages was subject to three powers: secular power (regnum), ecclesiastical power (sacerdotium) and the power of knowledge (study). Therefore, a ruler who would not support the development of science would be called a tyrant[3]. At the same time, European universities - whose sources are to be traced back to ancient thought, the Carolingian rebirth and the monastic movement - did not copy ancient models, Arab universities or the university in Constantinople established in 425. The organisational model of European universities was developed in two variants: Bologna and Paris and was the work of the medieval European spirit.

Those parts of Europe that were deprived of their own universities became dependent on the "power of knowledge" held in another kingdom. One can risk the claim that they were therefore symbolically "subjected" to foreign power in one third. This dependence on knowledge provided elsewhere had various dimensions: from the completely practical shortage of human resources and the need for burdensome and costly training of staff for the country abroad, to the political dangers associated with the lack of a description of the situation of one's own country and nation.

When we look back at the history of universities in our part of Europe, it seems as if from the beginning they were burdened with some kind of fate of secondary and dependence, a shadow of someone else's domination, the need to imitate and chase, to inscribe oneself in the currents that were driving the social and mental life of the West. This assessment is not false, but it does not tell the whole truth. Indeed, the political necessity caused the universities of Central and Eastern Europe to join the already accelerating and flowing wide river of study in the West like a stream. It soon became clear, however, that the efforts to create their own universities in this part of Europe were not only the result of efforts to increase their political prestige, but that combined with the authentic local customs (Greek: ethos) allowed the formation of sovereign minds and deeply connected with their own country. Eastern European thought, on the other hand, turned out to be a living and independent current. It supposed to transform soon, on the Council in Constance, into a clear whirlpool.

The great merit of the local university tradition is that it has been able to transform a certain necessitas (delay) into the virtue of an independent, non-corrupt search for what is right in the whole political field. Remaining in contact with universities in the West, she kept the awareness of the relationship with her own nation and did not stop asking questions about the currently desirable forms of service thereto. This raises the question of whether the universities of Central and Eastern Europe, especially Poland and Hungary, are still facing a similar task today. Shouldn't they be able to reclaim this role and make it more splendid? Should their primary function today be not so much a blind pursuit of Western thought and an "equation to" foreign research units, as asking traditional and current questions in a modern and autonomous way? Is it even possible to talk about research work where there is no sovereignty, and is it possible to talk about sovereignty where there are no objections? In a sense, academic mental effort is always the work of humility, which must be defined as healthy scepticism. The academic mind is to be immune to a kind of intellectual contamination that would lead to blind acceptance and repetition.

In the era of the undisputed primacy of liberal thought in the West, it seems that the renewal and maintenance of this scepticism, autonomy and mental sovereignty depends to a large extent on the change of social awareness. It was no different, as we explained earlier, in the Middle Ages. Automated, strong universities are the "emanation" of autonomous and strong nations. At the same time, they have a secondary impact on them, making it easier for them to fulfil their own aspirations. It is therefore fair to believe that a prerequisite for the success of the universities here is the maintenance of a political and social development and political transition that is not afraid to question the liberal paradigm of thinking and social praxis. It is also about not being afraid of the specific character of the local university thought. This is the way to be not only radiated, but also radiated. However, this is only possible where there is a living thought that is coloured with something peculiar. After all, it is impossible to radiate radiation on Anglo-Saxons with Anglo-Saxon thoughts, and on French with French thoughts. It is, of course, an academic duty to contribute to the debate with other centres. You can and should write a comment and a voice to their mental creations. You can expect comments and voices to your own thoughts. However, a particular risk is the desire for submission and imitation, waiting for a laurel instead of a review and a nod for a debate. Therefore, every mature nation (as well as every mature person) should use the measure of its own objectives and the fairness of the measures taken in order to assess its progress. Today, however, Central European universities are threatened by a certain degree of blindness in global terms. The appreciation on these measures is obtained mainly by joining the current that currently carries a modern mind. The Polish conservative thinker, Ryszard Legutko, clearly expressed the effects of this: "(...) in today's era, the triumph of liberal thinking in the humanities, in culture in general (including mass culture) is accompanied by a visible intellectual degradation, (...) a certain sterility, which has always threatened this direction, has become its main feature today. There is something disturbing about the fact that the same thought patterns today govern philosophy, theology, psychology and literary theory, and that the worldview language used by intellectuals in Los Angeles is the same as that used by their colleagues in Paris or other colleagues in Krakow. There is also something disturbing about the fact that the books of liberalism theorists or followers are slowly becoming indistinguishable from each other, despite the fact that ideologists of that direction promised the kingdom of diversity. Not only is this kingdom not coming, but there is such a unification of thinking that the scholastic period must appear as the time of intellectual anarchy[4].

If, as Legutko observes, there is a "unification of thinking", or rather a "unification of opinion". (as the view is less and less frequently the fruit of real thinking), the aim of the universities here should be to get out of the river. To make "the language of colleagues in Krakow" significantly different from the language used in Los Angeles or Paris.

The societies here are characterised by strong intellectual autonomy and historical awareness. They therefore seem to be an excellent subsoil for the renewal of the idea of a critical and free university that is at the same time rooted. The question that these societies are most obviously concerned with "how to defend themselves against unification of thinking" should today be the most fundamental question of their universities. By responding to them, these societies will find such a primordial university idea as their own roots. They will also become capable of being a force which, as Jagiełło wanted it, radiates, fertilizes, decorates, strengthens and explains. It's not about making science suffer here. It is only a matter of not thinking empty and arrogant, secondary and saturated with fashionable ideology. Central and Eastern Europe has the chance to become the backbone of true science and the restoration of the university idea.

I referenced the following:: F. Kiryk, Nauk przemożnych perła, series Dzieje Narodu i Państwa Polskiego, Kraków 1986; J.N.D. Kelly, Encyclopedia papieży, Warsaw, 1997 and R. Legutko, Od autora, in: the very same, Etyka absolutna i społeczeństwo otwarte, Kraków 1994.

[1] F. Kiryk, Nauk przemożnych perła, Dzieje Narodu i Państwa Polskiego, KAW, Kraków 1986, p. 55.

[2] Ibid., p. 61.

[3] Ibid., p. 26.

[4] R. Legutko, Od autor, in: the very same, Etyka absolutna i społeczeństwo otwarte, Kraków 1994, p. 8.

Justyna Melonowska –doktor filozofii, psycholog. Adiunkt w Akademii Pedagogiki Specjalnej im. Marii Grzegorzewskiej w Warszawie. Członkini European Society of Women in Theological Research. W latach 2014 - 2017 publicystka „Więzi” i członkini zespołu Laboratorium “Więzi”. Publikowała również w „Tygodniku Powszechnym”, „Gazecie Wyborczej”, „Newsweeku”, „Kulturze Liberalnej” i in. Od 2017 autorka „Christianitas. Pismo na rzecz ortodoksji”. Uczestniczka licznych debat publicznych