On July 22, French President Emmanuel Macron announced at a press conference in Paris that an agreement had been reached by 14 countries of the European Union on a temporary and voluntary redistribution mechanism for migrants taken on board European ships in the Mediterranean. Macron then once again threatened those countries that refused to take part in this “voluntary” scheme that France would no longer approve their receipt of EU structural funds. Although no specific country was named, the French media had no doubt that Macron was thinking of the Visegrád Four, and Hungary and Poland in particular. “As far as solidarity is concerned”, the French president said, “Europe is not ‘à la carte’. You cannot have countries saying ‘I don’t want your Europe when it is about sharing the burden, but I want it when it is about receiving structural funds’.”

A new Franco-German redistribution plan with similarities to the old compulsory relocation scheme

According to French sources, the temporary agreement reached in Paris is meant to avoid the endless squabbles over who should take charge of how many migrants each time an NGO ship conducts a new operation near the coast of Libya. It is based on the plan proposed earlier by German foreign minister Heiko Maas when he called for a “coalition of the willing” to replace the failed EU compulsory relocation mechanism. “We must now move forward with those member states that are ready to receive refugees – all others remain invited to participate,” Maas had said. On July 18, at an informal meeting of interior and justice ministers in Helsinki, Maas’s plan was proposed by Germany’s interior minister Horst Seehofer and supported by his French counterpart Christophe Castaner. France then organised the July 22 informal meeting in Paris with foreign and interior ministers from the “coalition of the willing”, as well as officials from the European Commission, the United Nations’ refugee agency and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Maas’s proposal was by then being presented as a joint Franco-German initiative.

However, only eight countries were actually named and said to have agreed to “actively” take part in such a voluntary redistribution mechanism. These are France, Germany, Finland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Lithuania, Croatia and Ireland. Macron said that “in principle, 14 member states, at this stage, have expressed their agreement with the Franco-German document”, but the other six countries who are supposed to have expressed their agreement have not been named and were nowhere to be found in subsequent media reports.

One thing is for sure: Italy was not among them. And this is good news for the Visegrád Group, as Macron’s statement about EU structural funds clearly shows that, in the minds of some European leaders, this so-called “coalition of the willing”, when it is further discussed at European level in September as planned by Paris and Berlin, is meant to become a new version of the former compulsory EU relocation scheme. As soon as Germany’s foreign minister made known his proposal for a “coalition of the willing”, it was dismissed by former Austrian chancellor Sebastian Kurz. His centre-right ÖVP party being the frontrunner to win the election in September, Kurz will probably soon become chancellor again. “The distribution of migrants in Europe has failed,” Kurz said on July 13, “we are once again discussing ideas from 2015 that have long proved impractical.” And he went on to explain that “the order of the day is rather to remove the business case for unscrupulous smugglers and return people after sea rescues to their home or transit countries, as well as creating initiatives for stability and economic development in Africa”, which is exactly what the Visegrád countries have been advocating since the beginning of the current migrant crisis.

In fact, not only would such a scheme take immigration out of the control of participating member states, but the discussions on the subject are sending a new signal to would-be emigrants in Africa and the Middle-East, and also to people smugglers in North Africa, that Europe’s gates are being opened wide once again, thus reinforcing the pull factor created by lenient policies in many European countries – not least in France and Germany, which allow most immigrants to stay and move freely around the Schengen area even after their requests for asylum have been rejected (see here for the figures as of 2018). At a press conference in Helsinki, French interior minister Christophe Castaner himself had to acknowledge that several EU countries fear the proposed voluntary redistribution mechanism will generate a new massive influx of migrants. This impression created by the likes of Maas, Seehofer, Castaner and Macron is further reinforced by the fact that NGO ships are now back in the Mediterranean, trying to force Salvini to reopen Italy’s ports to illegal immigrants, while France and Germany have also been making repeated calls for Italian ports to open up to boats transporting rescued migrants. The Franco-German mechanism which was agreed on in Paris on July 22 is still based on having rescued migrants disembarked in Italian ports and thereafter redistributed among participating countries. Similarly to the now defunct compulsory relocation scheme, the redistribution of migrants would only concern those asylum seekers who are likely to gain refugee status, and who are in fact a small minority of all illegal immigrants trying to cross the Mediterranean. According to the Franco-German plan, the remaining migrants would have to be kept in Italian centres until they could be deported. From the Italian point of view, there is nothing new in that proposal, and such a scheme will probably only increase the pressure on Libyan shores and increase the number of illegal immigrants making it to Europe, as well as the death toll by drowning in the Central Mediterranean.

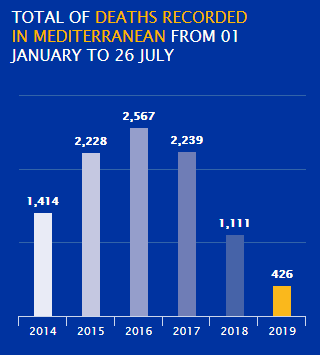

Total death toll from January 1 to July 26 each year (Central Mediterranean route only).

Source: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean

The Italian–Maltese plan

Italy and Malta came to the summit in Helsinki on July 17–18 with a different proposal. A day after Heiko Maas had first presented his own plan to the German RND media group, namely on July 14, Italy’s foreign minister Esteri Moavero Milanesi described his alternative plan in an interview with Corriere della Sera. What Rome and Valletta proposed was to give people the possibility of applying for refugee status as close as possible to their countries of departure, so that asylum requests could be considered before migrants illegally tried to cross the EU’s external borders. Charter flights would then be organised to safely take to Europe those who really deserved refugee status, thereby weakening the smugglers’ business model and avoiding unnecessary deaths at sea. Since the number of people reaching Europe in such a manner would be smaller and better controlled, a distribution scheme could be more easily agreed among EU member states. For those who nonetheless try to reach Europe illegally by sea, the joint Maltese–Italian plan requires the creation of controlled centres (“hotspots”) in all countries of the EU-28 and common policies to force the countries of departure to take their citizens back. It rejects the idea of having all migrants on the Central Mediterranean route landing in Italy before their relocation to other countries. It also calls for NGO vessels to be kept out of the search & rescue zones of Libya and other third countries.

Salvini to Macron: “Italy will not be France’s refugee camp”

This plan was rejected at Helsinki, as both Germany and France supported Seehofer’s plan. The League’s leader, Matteo Salvini, confirmed in a statement released on the day after a meeting in Helsinki on July 17 between ministers from France, Germany, Italy and Malta that the Franco-German proposal was unacceptable to Italy, as “simply redistributing refugees will leave hard-to-expel illegal immigrants in the first country of arrival”. And while Malta’s Prime Minister Joseph Muscat announced preparations for a new meeting between interior ministers of all four countries in Malta in September, France’s Christophe Castaner announced that he was inviting ministers from the “coalition of the willing” to Paris on July 22 in order to go ahead with the Franco-German scheme. This infuriated Italy’s Matteo Salvini, who refused to take part in the Paris meeting, choosing instead to send a “technical” delegation to block any new joint declaration. On July 19, Salvini wrote his French counterpart a letter in which he expressed his surprise at the fact that only the Franco-German proposal was to be discussed in Paris, pointing out that the Maltese–Italian proposal had “gathered broad support” among EU countries. In that letter, the League’s leader insisted again on the need to review the rules on search and rescue operations in order to put an end to behaviours which encourage illegal and uncontrolled immigration, and to make NGOs comply with both international and national laws. According to Salvini, many at the Justice and Home Affairs Council held in Helsinki had “positions very close to the one expressed by Italy, in particular as regards a strict commitment to a migration policy based on the protection of the EU’s and the Schengen Area’s external borders”.

After the announcement by President Macron of an agreement reached under his auspices and supported by 14 countries (of which only eight, including France, were named and said to be ready to

participate “actively”), Italy’s interior minister published a video on his Facebook profile with his own virulent reaction, mocking French leaders and saying directly to Macron, whom he called by his first name, that if he wanted ports open to migrants he should open France’s own ports in Marseilles, Corsica and elsewhere. He added that Italy would not take orders from France and would not be France’s refugee camp, as it is not a French colony.

Italy under pressure from France and Germany to take back illegal immigrants as per the Dublin Regulation

Salvini’s tone was no surprise to observers, who have been witnessing deteriorating relations between France and Italy since those whom the French president contemptuously calls “populists” and “nationalists” formed a coalition government in Rome over a year ago. Salvini’s mockery and verbal attacks have mostly come in response to Macron’s own highly arrogant and undiplomatic criticism of Italy’s leaders, particularly Matteo Salvini, which resembles some of the language he has used against the leaders of Poland and Hungary, as when he publicly asked last autumn in Bratislava: “What are these leaders doing with these crazy minds and lying to their people?”. Salvini’s anger is further fuelled by the fact that, while French leaders call for Italy to open its ports to migrants for humanitarian reasons, the French authorities have been enforcing border controls for years between Ventimiglia and Menton on the Mediterranean coast, and they send back illegal immigrants to Italy, including, according to some media reports, when those immigrants are caught at some distance from the Italian border, in which case such ‘hot returns’ are in breach of European rules. The Italians have also accused Germany of breaking the rules when returning migrants to Italy as per the Dublin Regulation (the so-called “Dubliners”). Apart from being asked by Germany and France to reopen its ports to illegal immigrants, as the first country of arrival Italy is under great pressure from other EU member states to take back some 46,000 immigrants. As a consequence of the mass disembarkation which took place under the auspices of Matteo Renzi’s government, the number of asylum seekers sent back to Italy has tripled in just five years, with most of the 188,000 requests for transfer made since 2013 coming from Germany, Switzerland, France and Austria.

To make things worse, on the eve of the Paris meeting of July 22, SOS Méditerranée, an NGO based in the French city of Marseilles, announced the launch of a new joint search and rescue operation together with the Franco-Swiss NGO Doctors Without Borders (MSF), using a new boat said to be larger and faster than the Aquarius, which has remained blocked at the request of Italian prosecutors. The Ocean Viking left the Polish port of Szczecin flying the Norwegian flag and heading towards Libyan shores. SOS Méditerranée and MSF estimate the cost of this operation at around €14,000 per day. In a press release published on July 12, the city of Paris had announced that it would contribute €100,000 to this expensive operation. The grant made by the French capital was announced at the same time as the award of a medal to Carola Rackete and Pia Klemp, two German NGO vessel captains who are facing serious charges in Italy for allegedly aiding illegal immigration, including – in the case of Klemp – through active collusion with smugglers.

France’s responsibility for the situation in Libya

The current situation in Libya is making things worse. Since April, when the Libyan National Army (LNA) launched an offensive against the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli, the hundreds of thousands of illegal migrants stuck in Libyan detention centres have seen their conditions worsen, and can now rightly be said to be fleeing a war zone when trying to board dinghies in the hope of being picked up at sea by a European vessel. To make things worse, the LNA is supported by France and the GNA by Italy, which since the summer of 2017 has successfully based its fight against illegal immigration on cooperation with Tripoli. Although France denies giving military support to the LNA, four Javelin antitank missiles formerly owned by the French army were discovered at an LNA base retaken by GNA forces at the beginning of July.

This comes eight years after France and the UK plunged Libya into chaos with the air strikes that resulted in the overthrow of the country’s long-time leader Muammar Gaddafi, a move which the Italians opposed at the time, not least because they feared it would open up Libya to a massive flux of migrants heading for Europe through Italy. And this is one more reason why Matteo Salvini will not take lessons in morality and humanity from Emmanuel Macron on the issue of illegal immigration.

It is also to be noted that Italy’s successful fight against illegal immigration through the Central Mediterranean has caused the northbound flow of migrants through Niger to drop by over 75% from an estimated 330,000 people in 2016. If Italy were to reopen its ports as per the new Franco-German redistribution scheme, it would most probably reverse this trend and thus increase the number of migrants trapped in Libya.

The common immigration policy Europe needs is the one advocated by Italy and the Visegrád Group

At the same time, while Spain has seen the influx of illegal immigrants increase dramatically since the arrival of socialist Pedro Sánchez at the head of the Spanish government in June 2018, Turkey announced last week that it was suspending the readmission agreement concluded with the EU in 2016. All this shows that a common European policy is badly needed, but it cannot be one that would reinforce the pull factor created by the facilitation of crossings to Europe while placing the main burden of illegal immigration on certain countries only.

As regards the Italian–Maltese proposal, it is worth recalling that Salvini, on a visit to Hungary in May, advocated the establishment of migrant hotspots outside Europe and harsh economic sanctions against countries of departure that refused to take their citizens back. He also said: “We trust that the new Europe from May 27 will protect its external borders, be they land borders, as in Hungary, or sea borders, like in Italy, because the problem is not to redistribute the migrants who are already here, but to prevent the arrival of thousands more of them.” This is exactly the stance the V4 countries have defended since the migrant crisis of 2015. On this occasion Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán also warned that Europeans would be better off listening to Italy and Hungary in this matter than to French President Emmanuel Macron.

The leader of the German CSU, to which Horst Seehofer belongs, said on his part that Orbán’s meeting with Salvini “is a bad sign” and that “there is not and cannot be cooperation with right-wing populists in Europe.” Later, in May, the German interior minister said very much the same thing, namely that he cannot trust people like his Italian counterpart Salvini. Poland, on the other hand, has been supportive of Salvini’s closed-port policy, just like Hungary.

It is therefore very clear today that on the issue of illegal immigration the EU has split into two main factions, one led by the Franco-German duet, and the other led by Italy and the Visegrád Group. With only eight countries having promised to participate actively in the new Franco-German redistribution scheme, the V4 now have a much better chance to win over a majority of EU countries than they did when only four countries (Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Romania) refused to sign up to the compulsory relocation scheme in September 2015. And let us not forget that, on that issue, the V4 has since been proven right, although not all will admit it. Italy is now on the side of the Visegrád Group and should remain so for the foreseeable future. Indeed, if the coalition between the League and the 5-Star Movement (M5S) were to collapse, opinion polls show that in the event of early elections the League would have every chance of leading a new right-wing coalition government like those they already have at local and regional level. Matteo Salvini and his League are there to stay.

Olivier Bault