We are left with the third pillar, the Roman and Latin element - the law. Speaking about him we will reach to St. Thomas because he perfectly synthesized the old Roman legal tradition with the spirit and precepts of Christianity - pax romana became in him fully developed pax romana christiana. And so, according to Aquinas, "the law is some kind of norm and measure of human conduct. Guided by it, one feels obliged to do something or to refrain from doing something. Therefore, the Latin name of the right - lex, derives from the ligarette - is associated, because it obliges to do (or not to do something)[1]. The principles of action, which the unreasonable creation has been instilled in the form of a compelling instinct, are presented to rational beings as the rules of law, referring to its freedom and reasonableness. But where is the human mind to take these norms from? The author of Summa theologians has no doubt that they are unsatisfactory and, moreover, have the highest possible establishment, being manifested as divine providence and as such also being known by reason:

"The world is governed by Divine providence and everything in the universe is governed by the idea of God. Therefore, the very idea of ruling things, which exists in God as the head of all things, is in fact its own law. And because, as we read in the Book of Proverbs, the idea in God does not arise in time, but is eternal, and therefore this law must be considered eternal[2].

The essence of the law is, therefore, its impermanence and transcendent legitimacy in that which exceeds the changing and unreliable human judgments and concepts. However, the law must at the same time be "compatible" with the nature of the beings concerned. God's law, therefore, does not violate the essence of man, but leads him to the highest goal - the good - in which he finds his ultimate fulfilment and therefore happiness. In so far as we know this eternal law, in so far as we have a "share" in it, because it concerns us, we can also recognize the natural law. For the creature "has a share in itself the eternal right. Thanks to him, there is a tendency for him to act properly and to aim. And it is precisely this eternal law, which exists in a rational creation, that is called the natural law[3]. So what we as humans recognize from the eternal law is called the natural law. Finally, we call 'particular regulations, developed by human reason, human law'. Of course, other conditions required from the essence of the law must be fulfilled". What's that? Of course, it is in conformity with the natural law, and thus with the Divine law (for the order of nature is established by God). Aquinas quotes Cicero's thoughts here with appreciation: "The beginning of the law (ius) is in nature itself. On the other hand, what reason thought was useful has become a custom. And finally, fear and inviolability of the law (lex) gave force to what came out of nature and custom"[4].

Thus, a purely human law (constituted) is the weakest in being and essentially dependent on natural law. The former therefore derives its credibility from compliance with the latter. Therefore, in certain circumstances, in the name of natural law it is possible and necessary to reject state laws. For example, we have the natural right to overthrow from the thrones and offices madmen, criminals, troublemakers or tyrants-all those who would like to establish moral norms themselves, regardless of the structure of being itself; those who would like to call black men white, and those who would like to do evil in the majesty of their offices and dignity. For the law is in the nature of things, God has put them there. And not only did he submit, but he allowed people to know: either directly through Revelation or through rational inquiries with this undeniable Revelation. Therefore, in order to maintain the pax, we must assume that there is a transcendent rule of law, that it cannot be arbitrarily established, even if it is established by a democratic majority or absolute ruler - otherwise we are condemned to what is called legal positivism. This one is expressed in the conviction that

The validity of legal norms results from their positive establishment or from the real social impact that the codified law is the only law, unlike the natural law, which seeks to subordinate the "ordinary" law to some supra-positive norms and to derive from the content of the latter the written law[5].

From this assumption, however, the positivists inevitably have further extremely worrying consequences:

"Legal positivism advocates the separation of law and morality [...]. The law does not require a moral assessment in order to be a law; therefore, a law may also be a law that is immoral[6].

We are well aware of the fatal examples of the application of the principle of separating the law from morality - just mention the legislation of Hitler's Germany or Stalin's Russia. Today, too, legislators often try to decide for themselves what is a positive value and what is a negative value, for example, let us look at disputes over abortion or euthanasia. In other words, legal positivism is based on moral relativism (conventionalism), and simultaneously legalizes it, lifting it to the level of the binding rule. We have known these mechanisms since the Sofist Trazymach of Chalcedon: the law is what the ruler wants to establish as law, what he has the power to promulgate and what he can enforce. The ruler will change - the law will change, perhaps even radically, because it only expresses the interest of the one who has power (it is not important whether we are talking about a single person or a group).

Certainly, such an approach to the essence of the law cannot become a support for any cultural and civilization community. On the contrary, it is a symptom of the deep disintegration of legal culture and the whole socio-political order. The law and the values it upholds must have supernatural legitimacy. Only then do they have real power and social trust. Values should have the power to have a real impact on human life, often completely rebuild it or even sacrifice it. But they have such a power only when we believe that they come "from on high", they are a revelation of the eternal, unchangeable elements of being. For who would sacrifice his life in the name of something which, by definition, is only a short-lived and changeable human law? The seriousness of the laws should stem from the fact that they keep things transcendent and perfect in their eternity. Legal positivism is the beginning of the end of every ordo. That's what happened in ancient Greece and Rome. That's how it is today.

However, it is not only the content of the law that is at stake. Equally important is its enforceability. Not even legislation when the state does not want or cannot create the tools to execute them will be of much help. Nothing undermines the authority of laws so much as their "paperiness" - the existence only in thick codes and textbooks for students. The offense must be prosecuted with all severity and seriousness. Anyone who breaks the law should not even have a shadow of hope that they will escape justice - although they are entitled to the fundamental right to a defence and a fair trial. But it must not be the case that there are crimes and sacrifices, and that the law and the justice system are unable to identify and punish the guilty. Ineffective law terribly corrupts society and also the justice system itself - it becomes only a tool of political coteries and interest groups. There can be no "more equal", "untouchable" or any "preferential options" or "cultural contexts" that make it possible for what we punish one another to go unpunished. Crime is to be prosecuted "until the end of the world", regardless of the dignity, influence or office of the culprit. The Pretorians of justice must inevitably knock on the right door at last. Fiat iustitia et pereat mundus - let the world perish as long as justice is done - this is the teaching left to us by the true Roman and also the father of the Church, St. Augustine. Did we preserve it and make it real?

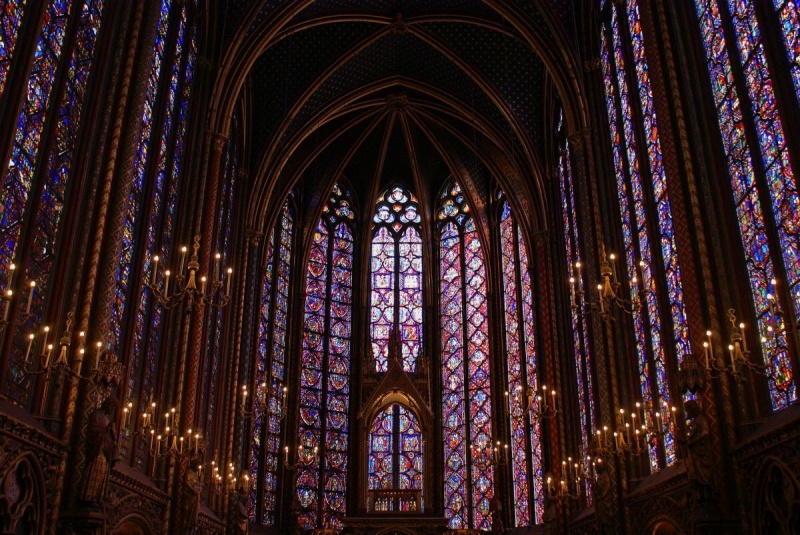

The legacy of Rome, however, is not only a law, but a certain broader idea of social security and order, as well as external (sensual) and internal (spiritual) beauty, which must remain the foundation and support of that order. It is also about the beauty of the common space - public buildings, squares, parks, streets and monuments - in order to live among it and allow it to refine itself on a daily basis, in public activity and in ordinary activities. We still admire the aesthetic beauty of Rome in the remnants that survived the fires of history. It is an expression of the desire for harmony between the Spirit and the body, between the public and the private, between the rational and the beyond. And the end of what is human with what belongs to the gods.

***

Let us note that these three pillars are indeed interdependent – if we remove one of them, the other will also falter as will, of course, that which rests upon them. When we cease to see the uniqueness of the human logos-mind, we also cease to believe in Transcendence-Logos, and when we cease to believe in it, we also reject the idea of the eternal moral law: Nomos-Logos. Then the social order is destroyed, and the only motive for individual and, what is worse, political actions becomes the instinctive pursuit of comfort, pleasure, "lightness" of being, or the power and wealth that make it possible. The end of the ethos, which is realized even at the cost of suffering and life, is a symptom of a serious social, cultural and moral illness. The desire for comfort, laziness, aversion to discipline and self-improvement, cynicism, where moderation and renunciation are alien, indifference to religion and the affairs of the homeland always preceded the fall of a given cultural and civilization formation in history. The question of the condition of the three pillars of the West today is, of course, a rhetorical one: it is clear that for three hundred years they have been systematically weakened and destroyed as alleged obstacles to progress, however it might have been defined. In recent decades, however, this process has significantly accelerated. Today, across the squares of the western world, there is a direct call for a final break with its historically developed legacy in the name of building on its ruins some other, "new and better" world. Today no one is hiding attacks on Christianity behind amenable sounding classical philosophy phrases or the idea of natural law. This implies that the struggle for the identity of the Western, Latin and Christian worlds has entered a decisive phase and that no one will be able to avoid opting for or against it any longer.

Bartosz Jastrzębski

Autor jest doktorem habilitowanym kulturoznawstwa, filozofem, pisarzem i etykiem, wykłada na Uniwersytecie Wrocławskim.

[2] Ibid.

[3] ST, I-II, 90, a. 2.

[4] Ibid., a.3

[5] L. Święcicki, Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss. Criticism of legal positivism in German political thought, Warsaw 2015, p. 37.

[6] Ibid.